What Seeds Are You Planting? The Care and Feeding of Pollinators

© Martha Wooding-Young, The Resilient Executive, LLC. A happy pollinator in the marigolds that protect the potatoes.

It’s no secret that to have a successful garden you need pollinators. The same is also true of business, we’re just not used to thinking about it that way. In the natural world, attracting pollinators is getting harder as their numbers dwindle alarmingly. The EPA has a SWAT team working on pollinator protection; their presence or absence is a single point of success or failure in our food supply. Chemical pesticides and fertilizers bear much of the blame, as does the biodiversity-destroying practice of genetically modified mono-cropping.

In the work world, pollinators are those people you love to bounce ideas off because their deep listening and open-ended questions make you think differently about the challenge at hand and surface creative solutions. My old boss was a great example. You could lay out a potential financing structure or a tricky client situation for him and he’d come back with imponderable questions that would reveal a totally different perspective. So how do you attract and care for human pollinators?

Here are a few of our farm’s pollinator tactics that translate well to the business world:

Remove invasive species. The pastures where prior owners kept horses and cattle were our first intervention: removing invasive species as much as possible and letting Mother Nature take over. I covered this in a recent article – no jerks, even talented ones! Having corrosive personalities on a team will drive pollinators away.

Rebuild the soil. As my husband mowed the (presumably GMO) pasture grasses, he carefully directed the hay onto bare areas of eroding clay. As mulch built up, erosion slowed, the soil started to recover, and the birds took care of the rest, naturally seeding a sea of native wildflowers. Rebuilding the soil at work is all about culture. As you take a good look at the culture you have created or in which you operate, do you like what you see? Sometimes you need to mulch: drop back, listen carefully, highlight and celebrate behaviors of team members that illustrate the purpose and passion of your organization. Sometimes you need to seed: investing in emotional intelligence training or team building can prevent culture erosion.

Avoid mono-cropping. Wall Street was careful about building diverse teams … but there was still a disproportionate number of HBS grads. Nothing against Harvard but having a bunch of people who went to prep school, Ivy-League undergrad, and then made it into the uber-competitive, Type-A extrovert gene pool of the top business schools, produces a bunch of similar answers. If you really want to foster creativity you need to consider not only demographic diversity, which is critical, but diversity of thinking and meaning-making styles. The best teams I ever worked on all had at least one serious introvert as well as a brilliant quant. You can also create and protect spaces for unplanned interactions between people with different backgrounds and responsibilities. This technique started in the dot com era and has been widely adopted in the modern office set-up. When the head of sales is in the coffee line talking to her buddy in the white-collar crime unit, who knows what unusual insights might flow in either direction?

Skip false solutions. Big agriculture genetically modifies crops to make them impervious to the big chemicals they rely on to fertilize and kill pests cheaply … and with terrible consequences. These chemicals are totally unnatural, and they seem to de-nature the food, already nutritionally impaired by genetic manipulation. Big companies also like to treat symptoms rather than causes. As a result, they often respond to the challenge of complexity by … creating further complexity. Instead of adding interlocking layers of compliance requirements, consider building and actively tending an over-arching ethical model that encourages the right kind of professional behavior without treating adults like middle-schoolers. Ask your most talented leaders to form a cross-disciplinary collaboration with legal and compliance to build the Occam’s razor of rule books. Then follow it. If you foster an ethical culture your employees’ understanding fills in for endless rulemaking (see Rebuild the soil above).

Build safety. We posted NO HUNTING signs all around the perimeter as soon as we got here. Our wildlife plays a critical role in the ecosystem from the deer and small mammals to the wolves and bobcats as well as the vultures, barred owls, and hawks. In a safe environment, these animals find an equilibrium where each species gets what it needs and is in turn held in balance by the others. It’s no Disney movie – the wildlife is wild, that’s for sure, but it’s illuminating to watch a balanced ecosystem at work. How can you provide the same safety for your team that we do for our wildlife? One way is to encourage experimentation and to see failure as a learning experience. We do this all the time on the farm – but in most work environments it is totally frowned upon. You either get it right the first time or risk a reputation hit. Many traditional businesses would do well to import from the tech world the practice of celebrating and harvesting lessons from failure. As NatGeo photographer DeWitt Jones says, adopt a “Win-Learn” attitude. Each failure is an opportunity – create a safe environment where lessons can be learned, and the knowledge gleaned can become part of the team DNA for the next project.

Provide nourishment. Make sure there’s food. We filled the half empty flower beds around the cabin with perennials known to attract bees, butterflies, and hummingbirds. From bee balm to yarrow, with echinacea, lavender, liatris, phlox, rudbeckia, sunflowers, and too many others to name, including flowering culinary and medicinal herbs, there is a veritable buffet for our pollinator friends to choose from. How can you keep your pollinators fed and happy? Consider creating a skunkworks to experiment in markets where your smartest leaders think your industry may be going next. Or build non-traditional roles where human idea pollinators can thrive. These roles may be hard to describe to your HR department, but the pollinators they attract build an invisible web of connective tissue (see Safety, above). The offbeat technical genius may be socially awkward but can model the most challenging problem in a way that gets people to think about it differently. That introvert may seem shy, but is listening intently to everything and can therefore hear things and make connections others miss. One thing human pollinators have in common is their total openness to experience – they positively exude curiosity. Daniel Coyle’s The Culture Code profiles a roving catalyst at design firm IDEO. She asks questions like, “What scares you about this opportunity?”, and “What’s one thing you’d like to get better at to make this idea work?” These folks are unlikely to apply for a more traditional role, so consider how you might build a role to feed their creativity. You might also offer leadership coaching to high potential individuals in your organization. A good coach is a confidential sounding board and can encourage individuals who have pollinator potential to open to change and to get better at receiving feedback as they make their way in an organization. A coach can encourage them to act and hold them accountable. A good coaching relationship is incredibly nourishing for a growing leader.

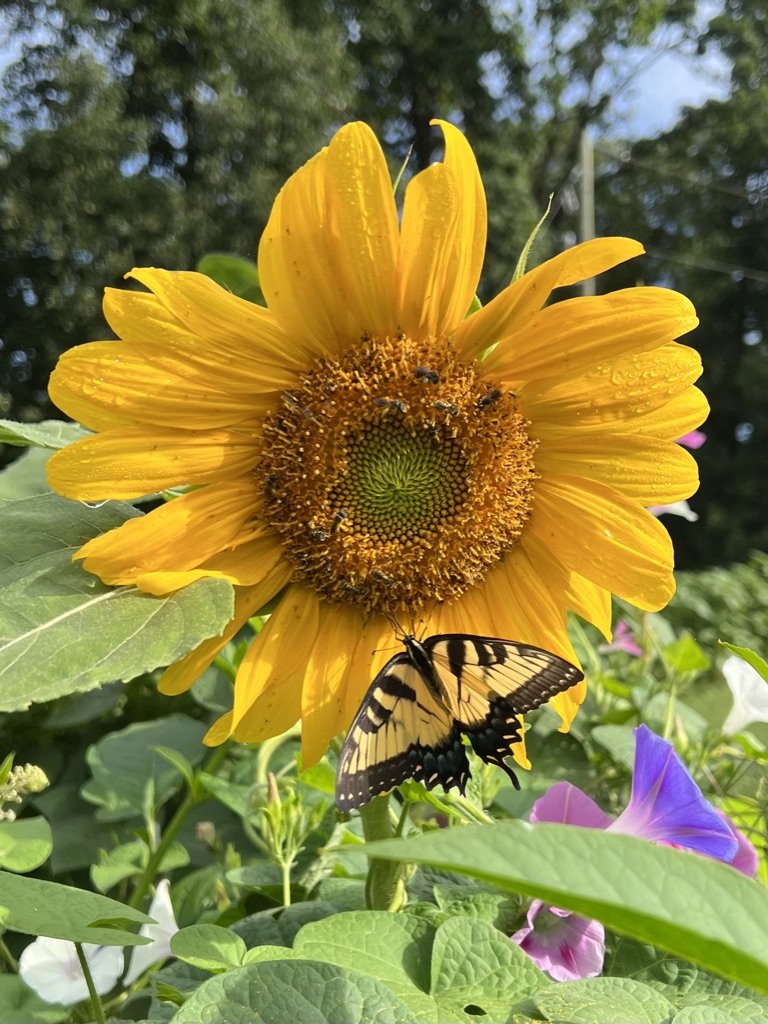

Practice companion planting. The marigolds pictured above are planted beside our potato bed where they attract pollinators and distract pests who don’t like the aroma. They also form the basis of one of the most effective organic pest controls. The sunflower at bottom is part of a mass-planted patch in the vegetable garden; the pollen attracts the pollinators and the seeds feed our song-bird friends. The lavender hedge that’s slowly forming along the southern fence of the veggie bed is a triple threat. It too brings the pollinators close to the vegetables, prevents erosion out of the garden, and provides harvestable aromatic buds to safely keep the moths out of our sweaters over the winter. It also looks and smells fantastic! Can you find ways to get people who wouldn’t normally interact to collaborate? My old boss was great at what he called “social engineering,” effectively, companion planting. He would take successful individuals who didn’t naturally interact and give them a national level problem to work on together. He also nurtured the close collaborations that sprang up organically, allowing people to grow where they naturally thrive.

In our third summer at Heartwood, we have meadows filled with 6 types of clover, field madder, buttercups, wild salvia, motherwort, wild geranium, and speedwell to name a few of our favorites. When we walk the dogs in the morning, other than the sound of our many birds, the most constant soundscape is the buzz of the solitary pollinators and bumble bees in the wildflowers. It’s the soundtrack of a happy, balanced ecosystem. Want to talk about how to attract pollinators to your leadership team, or providing coaching to the potential pollinators already there? Reach out.

© Martha Wooding-Young, The Resilient Executive, LLC. Pollinators at work in the garden.